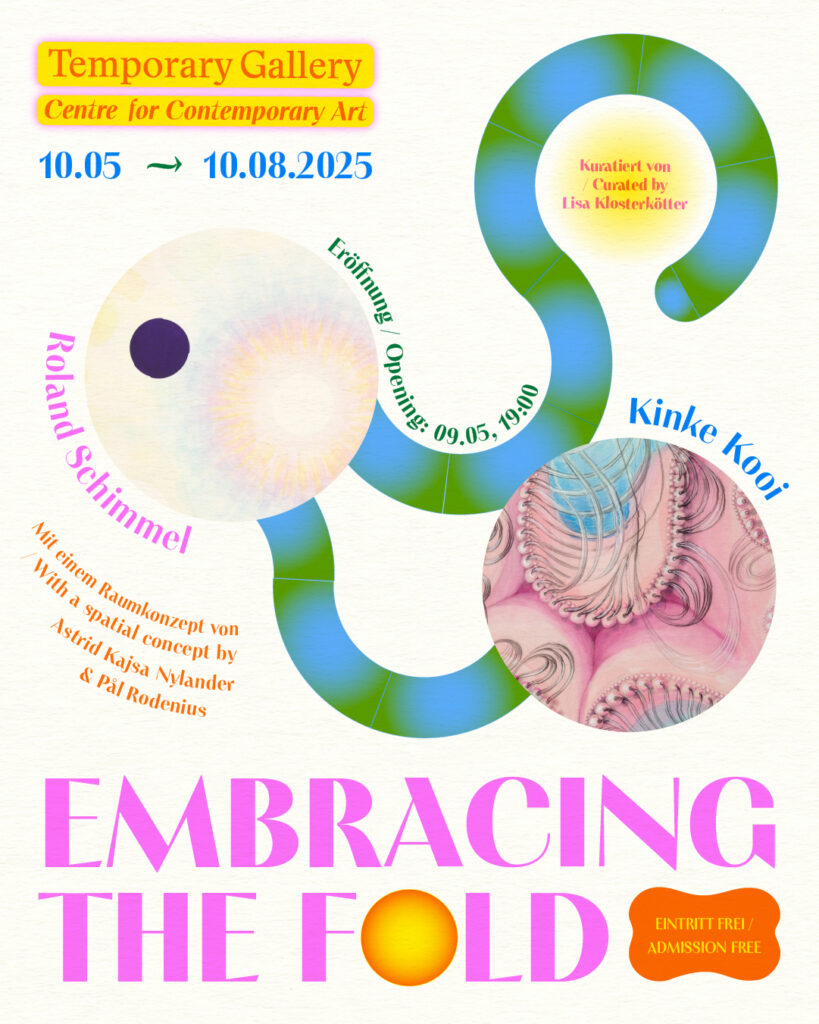

EMBRACING THE FOLD

Kinke Kooi and Roland Schimmel

10 May — 10 August 2025

Opening: Fri 9 May, 7 p.m.

Short info in plain language

Kinke Kooi and Roland Schimmel are two artists from the Netherlands. Although they have lived and worked together for almost 40 years, they have never exhibited their art together before. This is surprising, as their works complement each other well. The two of them say that their art was created in an exchange with each other. They have influenced each other. Now, they are showing their artworks together for the first time in Temporary Gallery. There you can see:

– Paintings

– Drawings

– Computer animations

– Collages

– Wall painting

The exhibition has an English title. In German this translates to: “Umarmung der Falte” or “Falte umarmen.” The title fits well with the exhibition because the images by Kinke Kooi and Roland Schimmel are often about folds: You can see the folds in the pictures – as painted lines and shapes. But is it also about an idea – a fold can be something that makes you wonder, like in philosophy.

The exhibition aims to evoke a feeling of warmth – like finding yourself in the embrace of a fold. This also shows what the two artists have in common.

The artist Astrid Kajsa Nylander and the designer Pål Rodenius have developed a special idea for the exhibition space. Among other things, it includes pieces of furniture and a carpet.

This idea links the artworks in the room even more closely together. The room feels open and invites everyone to stay, to feel comfortable, and to reflect.

Fold

A fold is always folded within a fold, like a cavern in a cavern.

The baroque house has two stories. A tower in the middle of the building forms the upper floor; narrowed, round, and winding, or angular with a gable: closed private room, decorated with a ‘drapery diversified by folds.’ The ground floor is elongated and square. It comprises common rooms with ‘a few small openings’: the five senses.

When I visited Kinke Kooi and Roland Schimmel for the first time in Arnhem in the winter of 2019, I encountered this very baroque house. Two studios on top of each other. Upstairs, images full of folds, pockets, tunnels, slits, layering, frills, and caverns. And downstairs, a pictorial world that unfolded in spheres, light sources, rays, reflections, stains, flickers, fixed points, and openings.

A few years later, I discovered The Baroque House (An Allegory) in The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, an image that I could not only connect with Kooi’s and Schimmel’s shared home and workspace but which also seemed to represent a kind of alignment or crossover between their two ways of working and thinking. The two floors are architecturally separate and yet they are under the same roof. In most houses, a staircase connects them. It is certain that there is communication between the two levels (which is why content rises up into the soul), Deleuze writes.

In The Fold French philosopher Gilles Deleuze examines how baroque thought is not linear but curved, folded, and multilayered. The world does not consist of fixed and self-contained things but of a continuum of transitions, of foldings – like fabrics that can be folded into an infinite number of creased layers. He finds this thought exemplified in the work of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, particularly in his concept of the Monad: an internal, closed center of perception, a microcosm of sorts that contains everything needed to experience the world from a personal perspective. The idea of the monad is a concept for understanding how Leibniz saw the universe as a system of deeply interlinked units, reinforced by their interconnectedness and thereby independent. The world is not made up of self-contained units, as it were, but of infinite foldings. The fold describes transitions, differences, dynamics, and bridges between the internal and the external, subject and world. The fold demands a way of thinking that places complexity, difference, and processuality at the center, instead of fixed, linear identities or simple dualisms.

The exhibition Embracing the Fold has slipped into a fold, protectively enclosed by a seam, enveloped, encompassed, embraced; it is an entanglement, a connection, a transition, between the just-before and the just-after.

Just before immersing myself in the density of Kinke Kooi’s drawings – I imagine how my face descends very near to the floral forms, as if into a bouquet of flowers, deeper and deeper, sinking into a warm cushion, becoming heavier and enveloped – more ornament, more protection, more adornment more greed.

Then the fog lifts, and the gaze wanders on, drawn into the pictures by Roland Schimmel. They revolve around the idea of the after because all that remains is an afterimage, a flickering, whirring, wafting. Where Kooi’s works evoke the feeling of being just before something, Schimmel’s works are what appears before the eye afterward, even if only briefly, and lingers on.

Together, the works of Kinke Kooi and Roland Schimmel form a breath, a two-step movement that flows towards one another: contracting and expanding, folding and smoothing out again, shrinking and swelling again, drawing in and spreading out.

The relationship between Kooi’s and Schimmel's works is like a reversible figure, an inversion, a reversal from large to small, from the outermost to the innermost and back again. Roland Schimmel’s precisely placed, molecular circular forms find their counterparts in Kinke Kooi’s hand-drawn round pearls, berries, and fractals, in the natural and artificial objects and structures of her paintings. It is as if a temporal shift or a degree of abstraction has come between the two.

The fold also appears in Kinke Kooi’s works as folds of shame and simultaneously as folds of self-empowerment. Depicted as a vaginal fold, a wrinkle, or a belly crease, it dissolves stereotypical ideals of beauty as well as unsettles the taboo of the female desirous body, which has been suppressed and made invisible for so long.

The fold also functions as a hiding place, a retreat, and a shelter. In an interview Kinke Kooi has said: I come to the rest in the holes of shame, as it were. I live in them for a while, I explore them. She often describes how in the early 1980s, when she was studying at the Art Academy in Arnhem, her decorative, curved, excessive forms opposed the idea that minimalism and rationality were superior. This resistance resulted in a strong position that still permeates every pore of her rich body of work today, reappropriating what has historically been dismissed as a “feminine” aesthetic. For her, this process also involved feelings of shame and an impulse to withdraw, which she continues to thematize in her work.

Kooi’s work engages with the fold in a way that relates to body awareness and also to the challenging of hierarchies: the way the elements in her work intertwine and expand suggests a non-hierarchical, interconnected world, in which no singular form dominates – this can be read as a metaphor for feminist ideals of relationality and care and builds a bridge back to Deleuze, who, however, omits this aspect of the “care-work of the fold”.

Roland Schimmel’s paintings take up the fold less in its physical materiality and more in its perceptual dimension of expansion and contraction. His work does not only exist on the surface, but folds into the retina, into memory, into the nervous system, and renders perception an unfolding process. The way in which colors and color transitions dissolve edges and create optical instability points towards a folding of space and time in which vision is not fixed but constantly shifting. The dynamic play of light and perception in his work creates an intensity similar to how Deleuze describes the baroque fold as energy that moves through space and bends reality itself. Schimmel’s work folds perception into the body and anchors it in memory, afterimages, and neurological processes.

Just as Kinke Kooi’s folds articulate a feminist ethic of care, equality, and embodiment, Schimmel’s perceptual folds, by dissolving fixed visual structures, may also hold a kind of radical openness, a suspension of control over vision itself. This embrace of the fold brought about collectively through artistic processes, points to a fluid way of experiencing the world –one that defies the strict categories of its time, rigid hierarchies, and fixed perspectives.

Extension

The soul is extended everywhere along the body, says Descartes; it is entirely everywhere all along it, on its very surface, insinuated within it, and slipped into it, infiltrated, impregnating, tentacular, inflating, modeling, omnipresent.

As a counter-movement to folding, the works of Kooi and Schimmel also reveal an unfolding – the potential of extension.

In his work, Robert Schimmel reflects on the term “hyperdifferentiation” (Brian Massumi). For him, this refers to the idea of an inexhaustible space of possibility that on a virtual level already contains everything. If light represents this universal potential in his work, color could be considered its initial extension – just as colors appear when light passes through a prism. Schimmel imagines that the human eye retains a bio-cosmic memory of an original and hyper-differentiated light that people take in as newborns – a kind of “inner” light. He believes that afterimages arise from the reservoir of this “inner light”. They establish a physical connection and balance a constantly changing specific actuality (colors as they appear in the environment i.e. reality) with its potential unfolding. In a sense, they form a bridge between the body and the soul.

In other words, afterimages are deeply relational and connect different parts back to a hyperdifferentiated, universal whole. In that sense, they can have a healing quality for Schimmel. However, their sparkling and frenetic appearance can also evoke a sense of powerlessness or loss of control that can be at once frightening, challenging, and exciting.

The distance between an image and what it represents is rendered obsolete by the short-circuiting effect of the afterimage in time and space. Afterimages, like gravitational waves, are a physical reminder of a distant cosmic past. Roland Schimmel says that for him, his work functions like an exercise in consciousness and attunement to the constant interplay between the universal and the specific – it places a specific temporality in a broader and more universal perspective.

Kinke Kooi describes her way of working as an act of filling and spreading and compares it to the behavior of water. For, water has no shape of its own and is radically adaptable to any other form. Water always flows to the lowest point and fills even the smallest openings without leaving any gaps. Kooi says that her way of drawing can be described as a process of adaptation – filling the space between things – which enables her to touch everything, to be in contact with everything at the same time. This expansive connectedness brings with it something electrifying, sensual, and overwhelming, for the artist herself as well as for the viewers.

Another quote by Gilles Deleuze illustrates the processual extension from within, which Kinke Kooi describes in similar terms. Matter thus offers an infinitely porous, spongy, or cavernous texture without emptiness, caverns endlessly contained in other caverns: no matter how small, each body contains a world pierced with irregular passages, surrounded and penetrated by an increasingly vaporous fluid.

I recall a conversation with both artists a few months ago. We exchanged ideas about the perception of space and the feeling of seeing the proportions of the surroundings slip away from one point in the room. Lying in bed just before falling asleep, in semi-darkness. The body becomes smaller, contracts – as if in the navel of the room, our limbs slide together at a low point. The room, in turn, takes up space, unfolds, extends to the sides, opens up into infinity, and with it all the shapes, rays of light, and shadows that follow.

Greed

Let me start by disarming the word straight away: of course, I am not talking about greed as a mean, avaricious, destructive energy, but rather about the urgent, relentless longing for more. Because this is a feeling that the works of both artists evoke strongly in me. Nevertheless, I speak of greed because it feels more appropriate to stick my neck out with this choice of words. The greed I feel is a hunger for the tiny, fragile, delicate, for everything that glitters and sparkles, shines and bites, for the endlessly open, for the universal, for opening my eyes wider and wider or squeezing them tighter and tighter to be able to recognize even the smallest detail in its subtlety and sharpness. It is the persistent desire to sink in, to dive under, to disappear, to be able to touch everything, to be sucked into an immersive, perhaps even psychedelic experience.

Coming and going in epochal spurts, this greed for real feeling, for extremes such as excess and reduction, has repeatedly taken hold of people. And it is very relevant today.

Kooi’s and Schimmel’s works, in all their differences, find themselves together in a fold somewhere in between. Between hustle and meditation, and are thus an incarnation of what drives such greed.

Another interesting thing is that after all these attempts to collect my thoughts and put them into words, Schimmel’s works can seem surprisingly representational and Kooi’s works sometimes appear very abstract to me.

Text: Lisa Klosterkötter

Footnotes:

1—The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, p. 5., Gilles Deleuze, 1993

2—The Baroque House (An Allegory). In: The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, Gilles Deleuze, 1993

3—ibid.

4—Corpus, p. 150, Jean-Luc Nancy, 2008

5—The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, p. 5. Gilles Deleuze, 1993

The artist Astrid Kajsa Nylander and the interior architect Pål Rodenius have jointly developed a furniture and spatial concept for Embracing the Fold. Drawing from Nylander's painting and Rodenius' design practice, they explored ways to bring their respective artistic expressions into resonance with the works of Kinke Kooi and Roland Schimmel. The design of a series of benches is based on the thread and button motif from Nylander's series Minijobs – a series of paintings the artist has been working on since 2016. Inspired by childhood memories of her grandmother's button collection, the button becomes a central element – ordinary and functional, yet also a small technical marvel that connects and holds things together. Buttons also appear in Kinke Kooi’s drawings and find an echo in Roland Schimmel’s circular afterimages.

For the exhibition at Temporary Gallery, Nylander and Rodenius designed a winding thread as a modular bench. The thread can link elements but can also unravel, come apart or divide. A freestanding button in the space functions as a low table for play, crafts, or writing.

The spatial design contributes to an immersive setting in which the exhibited works become more tightly interwoven and offer a shared experience. The exhibition invites visitors to spend time and gather their thoughts.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander (*1989 in Gothenburg, Sweden) works with performance and installation in pieces that can be described as interpretations of painting in an expanded field. Her painting series Minijobs was exhibited at PAGE (NYC) in New York and is part of the Moderna Museet’s collection. In 2019, Nylander received the Stiftung Sparkasse Siegen Prize, followed by a solo exhibition at Kunstverein Siegen. Together with Helena Lund Ek, she runs Painting Practice – a forum for painting that includes artist talks, exhibitions, readings, and workshops.

Pål Rodenius (*1982 in Visby, Sweden) is an interior architect and designer. He critically engages with questions of form in order to develop a broader perspective on what form represents or communicates. His methods span multiple scales and forms of expression, including interiors, furniture, and sculpture – often featuring traces of craftsmanship. With a focus on materiality, economy, and social perspectives, he strives to develop sustainable processes in which pedagogy and the collective power of shared knowledge and experience are key components. Rodenius works as a lecturer in Interior Architecture and Furniture Design at Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm.

Kinke Kooi (*1961 in Leeuwarden, Netherlands) is known for her detailed drawings, which bring forth subtle, organic forms with an almost tactile presence. Her works address issues of intimacy, physicality, and language, characterized by an opulent, often hypnotic aesthetic. Kooi is one of the most prominent contemporary artists in the Netherlands. She has held numerous solo exhibitions in renowned institutions such as the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Museum Arnhem, the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, and the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs. She is represented by the galleries Lucas Hirsch in Düsseldorf and Galerie Adams and Ollman in Portland. Her works are part of important collections, including those of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Sammlung Goetz in Munich, and the Philara Collection in Düsseldorf.

Roland Schimmel (*1954 in Hooglanderveen, Netherlands) creates works that explore the perception and interaction between the human eye and the brain. In his paintings, murals, computer animations, and installations, Schimmel investigates how visual phenomena such as afterimages arise and the role they play in our understanding of reality. One example of his work is the mural The Innocent Eye, which he created in 2012 for the courtyard of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. In this installation, he directs the viewers' perception by incorporating the sunlight itself into the design. Schimmel has exhibited at, among others, the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. He was also commissioned to create a site-specific mural for the Dutch Embassy in Kyiv. He received the KNAW Prize for Astronomy and Art. His works are part of various collections, including the art collection of the Haagse Hogeschool and the ABN Amro Collection, the collection of Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Centraal Museum, Utrecht and the Stedelijk Museum Schiedam.

Images:

Embracing the Fold, Kinke Kooi und Roland Schimmel, Raumkonzept und Mobiliar von Astrid Kajsa Nylander und Pål Rodenius, Installationsansicht, Temporary Gallery. Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst, Köln, 2025.

Photos: Simon Vogel

Embracing the Fold, Grafikdesign: Gabriella Marcella, Risotto Studio

Funding and support:

Kulturamt Stadt Köln

Kunststiftung NRW

Mondriaan Fonds

Generalkonsulat des Königreichs der Niederlande in Deutschland